Older medicines for multiple sclerosis get more expensive with each new therapy developed

By John Tozzi

This article originally appeared in Bloomberg Business: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-04-24/health-the-price-of-multiple-sclerosis-drugs-only-goes-up

Imagine Apple’s first iPhone is still on sale today. Now imagine it costs many times its original price of $599, and that the price goes up every time a new, competing phone is released.

That bizarro world is what the market for multiple sclerosis drugs looks like, as described in a new paper in the journal Neurology. And doctors are calling for it to change.

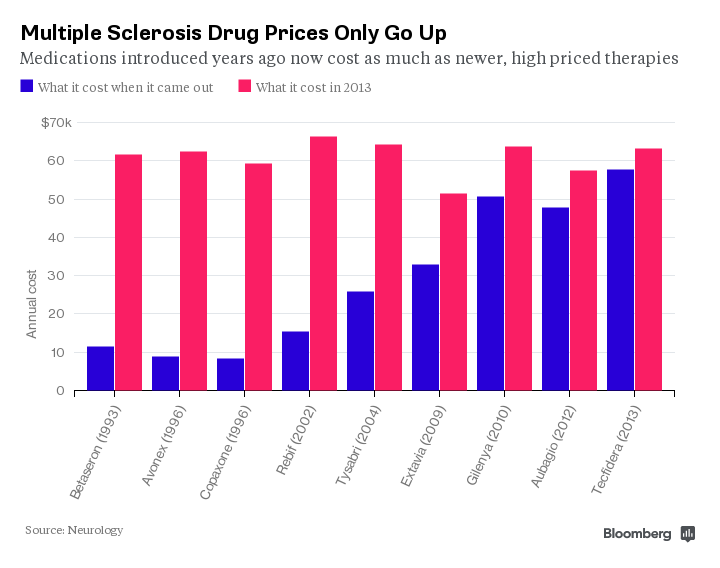

MS is a chronic disorder of the nervous system that afflicts about 400,000 Americans with a variety of symptoms, including fatigue, difficulty moving, and vision problems. When the first therapies to treat MS were approved in the 1990s, they cost $8,000 to $12,000 a year. Subsequent drugs entered the market with higher prices. The competition didn’t drive down cost, as Economics 101 would predict. Instead, the prices of the older drugs increased and rose several times faster than the overall rate at which drug costs increased.

Here’s a chart of how much each of the MS drugs in the study cost when they hit the market and how much they cost in 2013:

Now all the MS drugs cost between $50,000 and $65,000 a year, including the ones that went for less than $10,000 when they made their debut. “Our data suggest prices of existing [therapies] paradoxically rise, quickly matching prices set by the newest competitor,” the authors, from Oregon State University and Oregon Health & Science University, write. (The paper left out the two most recent MS therapies because data weren’t available. It also excluded one older drug that’s rarely prescribed for MS because of safety concerns.)

A lot of the recent discussion about drug prices in the U.S. has been about expensive new therapies for the liver disease hepatitis C. Those pills are highly effective, curing most patients after a course of a few months, and manufacturers have argued that the high prices are justified, especially if they avoid more costly treatments, such as liver transplants, later on.

There is no cure for MS, though, and patients typically take medication for years or decades. The changes in price for older drugs matter because those drugs are often widely prescribed. Copaxone, approved in 1996, is still the bestselling MS therapy, with 2014 retail sales of $3.4 billion in the U.S., according to data from Bloomberg Intelligence.

The new analysis in Neurology is based on the drugs’ average wholesale prices—essentially the list price. Health plans typically negotiate discounts off that price. “Nobody’s paying the list price,” said Robert Zirkelbach, spokesman for the drug industry group Pharmaceutical Research & Manufacturers of America, who had not seen the study. “As you have more players in the marketplace, insurers and pharmacy benefit managers are able to negotiate even steeper discounts.”

Other data supports the Oregon researchers’ analysis. The three MS drugs approved in the 1990s—Bayer’s Betaseron, Biogen’s Avonex, and Teva’s Copaxone—had total U.S. sales of $2 billion in 2006, according to Bloomberg Intelligence data that track what pharmacies pay wholesalers. That figure tripled to more than $6 billion by 2014, even as several competing therapies were approved.

The price hikes seem to move in lockstep, as this chart from the Neurology article shows.

It’s not clear why the cost of MS drugs is increasing so much faster than drug prices overall. There are no generic versions of MS therapies on the market, as there are with many other classes of drugs, and generic competition often brings prices down. (The first MS generic, a version of Copaxone, was just approved. It’s unclear when it might reach the market.) The MS drugs are also part of a complex category of drugs known as biologics that are more difficult to develop and manufacture than traditional pharmaceuticals. Still, the researchers compared MS with another set of biologics, used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, and the prices for MS increased much faster.

The researchers decided to look at MS drug costs after two neurologists at Oregon Health & Science University had trouble getting medication for their patients, said Dan Hartung, the study’s lead author and an associate professor at Oregon State. “We have a market for health care and pharmaceuticals that tolerates, at least up until now, fairly high prices for medication,” Hartung said.

That may be changing. While insurance companies and patients have long complained about high drug costs, physicians are increasingly joining them. Doctors at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center denounced expensive cancer drugs on the New York Times op-ed page in 2012. Doctors have also taken to academic journals to argue for lower prices for leukemia drugs. In an editorial in Neurology accompanying the study, two Canadian researchers call what’s happening in the MS market a brazen money grab by the drug industry.

“Like big banks, pharma cannot be free to ravish the marketplace unfettered,” they write. “There is a need at times to grab the big banks or big pharma by the lapels and make it clear that they are seriously out of line and are hurting people.”